From Abracadabra to Zombies

Skeptimedia

Jamy Ian Swiss, TAM 2012, and Cognitive Incompetence

Date. 14 August 2012

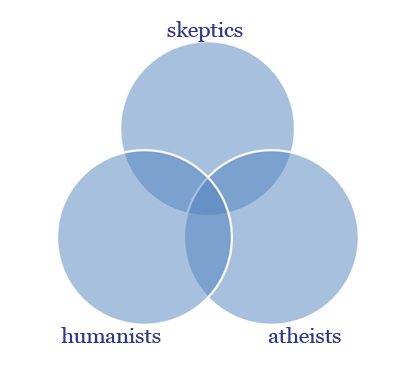

Like many of you, I didn't attend TAM this year. I read several reviews of the event that praised the talk by Jamy Ian Swiss as "passionate," "inspiring," and "the best of the bunch." Orac posted a video of the talk. It's well worth the 30 or 40 minutes to listen to what Jamy has to say, but he hints in his talk that a Venn diagram could explain much of it much more simply and much more quickly. So, I whipped up the diagram using PowerPoint and Photoshop. Here it is; the explanation follows.

Like many of you, I didn't attend TAM this year. I read several reviews of the event that praised the talk by Jamy Ian Swiss as "passionate," "inspiring," and "the best of the bunch." Orac posted a video of the talk. It's well worth the 30 or 40 minutes to listen to what Jamy has to say, but he hints in his talk that a Venn diagram could explain much of it much more simply and much more quickly. So, I whipped up the diagram using PowerPoint and Photoshop. Here it is; the explanation follows.

Each circle represents a set. Overlaps represent sets with shared characteristics. Jamy's point was that the set of skeptics isn't confined within the set of atheists or the set of humanists. Only some skeptics are atheists or humanists or both. If you wanted to add the set of critical thinkers to this diagram, you would need a circle within and smaller than the skeptic's circle because all critical thinkers are skeptics, but not all skeptics are critical thinkers. If you do not think that all critical thinkers are skeptics, you probably don't understand scientific skepticism. It is not a set of beliefs, but a set of attitudes and approaches to inquiry. The critical thinker set would overlap with both the atheist and humanist sets because some atheists and humanists are critical thinkers but not all are. (For a more detailed account of the Venn diagram above, click here.)

Bill Maher was fingered as an atheist who is not a skeptic because of his views on vaccinations. (Maher also has some unscientific views about germs and the role food plays in disease, but Jamy didn't hammer on those ideas.)

Finally, if you were to add a circle for the set of theists, you would need a circle outside of the atheist circle (since no theists are atheists) but which overlaps with the set of skeptics and critical thinkers. (Humanists can be either secular or otherworldly, but that is beside the point that Jamy was trying to make.)

Swiss's conclusion seems to be that the skeptics' tent includes some theists--those who are skeptical and critical thinkers--and also includes some people most of us wouldn't want to be associated with because they are not critical thinkers, even though they don't believe in anything paranormal or supernatural.

I agree with Jamy and would add that there are some skeptics who may not believe in anything paranormal or supernatural, but they may be contrarians or denialists who have a political agenda that drives their rationalizations about global warming, vaccinations, organic food, and a host of other things. They may be uncritical thinkers who know very little about the cognitive illusions and biases that lead us astray. Worse, they might not care to study or learn about those illusions and biases. They may prefer to go through life guided by their intuitions and a belief in their infallible ability to understand their own experiences without the help of scientific knowledge.

About the only place where Jamy and I disagree is on the value of the concept of cognitive dissonance as an explanatory concept. I prefer 'cognitive incompetence' to explain why people believe weird things when confronted with strong evidence against their weird belief. Think about it. 'Cognitive dissonance' doesn't explain why a person chooses the weird belief over the rational one when confronted with the evidence. Isn't that what we're interested in? You might as well say that the person who gives up a weird belief when confronted with strong evidence against it is also doing so because of cognitive dissonance.

Consider the case of the chiropractors who agreed to a randomized double-blind control group test of applied kinesiology (AK). When their weird belief failed the test, they not only didn't give up their weird belief, they rejected the value of scientific testing. Why? Cognitive dissonance? What if they had changed their mind about AK? Would that have been due to cognitive dissonance, too? Anyway, I think it is more fruitful to look at these kinds of cases as example of cognitive incompetence. These chiropractors are not stupid; they're probably of average or above average intelligence. But they don't know how the mind works. They're ignorant of the psychology of belief, of the many cognitive biases and illusions that deceive us, and perhaps of a few logical fallacies. The reason I can't change their minds is because of their cognitive incompetence, not because of cognitive dissonance.

The issue that interests me, anyway, isn't why I can't change the minds of the chiropractors who would dismiss randomized double-blind control group studies as worthless because they disconfirm AK, which they know from experience is true beyond doubt. I'm interested in showing others why these guys are wrong. I won't influence any bystanders by explaining the chiropractor's rationalization as due to "cognitive dissonance"--the attempt to avoid the psychological discomfort of holding conflicting views. I might influence some bystanders, however, if I explain the chiropractor's rationalizations as due to some cognitive biases that affect all of us from time to time. In this case, it is likely the chiropractors engaged in some faulty causal reasoning from their experiences involving the testing of applied kinesiology. There's probably a healthy portion of confirmation bias and self-deception going on as well.

My interest in exploring and explaining cognitive biases and illusions, along with logical fallacies, has led me to focus on another blog these past 35 weeks. Unnatural Acts That Can Improve Your Thinking is a follow-up to my latest book Unnatural Acts: Critical Thinking, Skepticism, and Science Explained! Every Monday I post another entry. I hope some of you will read a few and add your comments.

postscript: If you like skeptical meet-ups like the Amazing Meeting, you might like CSICon coming up on October 25-28 in Nashville.

Detailed explanation of the Venn diagram for atheists, humanists, and skeptics

Note: the areas designated by letters are not meant to be proportional to the size of the set they represent nor should it be assumed that any set represented here must have at least one member.

a= skeptics who are humanists and atheists (i.e., secular humanists who are skeptics)

b= skeptics who are humanists but not atheists (e.g., skeptics who are humanists and deists)

c= skeptics who are atheists but not humanists

d= humanists who are atheists but not skeptics

e= skeptics who are neither humanists nor atheists

f= humanists who are neither skeptics nor atheists

g= atheists who are neither skeptics nor humanists

h= all those who are neither skeptics, humanists, nor atheists (e.g., Islamic jihadists)

Jamy's point: The skeptic tent includes humanists, non-humanists, atheists, and non-atheists. Some of us who are skeptcs and secular humanists identify more with skeptics than with either humanists or atheists. Secular humanists who are skeptics might identify more with atheists or humanists than with skeptics, but they shouldn't forget that there are skeptics who are neither atheists nor humanists.